Photo from zIDEAz

Every time I start to get discouraged with this project – thinking, perhaps, it's too obvious, self-evident, or unoriginal – I find things like this transit... center... thing proposed for San Bernardino. There's an (I think) unintentionally hilarious sales pitch in the comments at California HSR Blog:

San Bernardino recently unveiled plans for the best-designed high-speed rail station in California that has the capability of becoming a high-speed train hub for service to Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Anaheim-Long Beach, in addition to Los Angeles and San Diego.

Passengers will enter the terminal though the Great Hall, a multi-story concourse with ticketing facilities, escalators, and a green roof on the fourth level that will serve as a park offering dramatic views of the city’s mountains and skyline.

A Central Garden runs along the edges of all the at-grade tracks. Mixed-use development is seamlessly-integrated throughout the terminal with a residential emphasis South of the tracks and an employment emphasis North of the tracks. A generous amount of meeting and convention space is also included in the design. But, the complex does a remarkable job of amassing these facilities without creating a superblock since a network of interconnected streets are interwoven throughout the site.

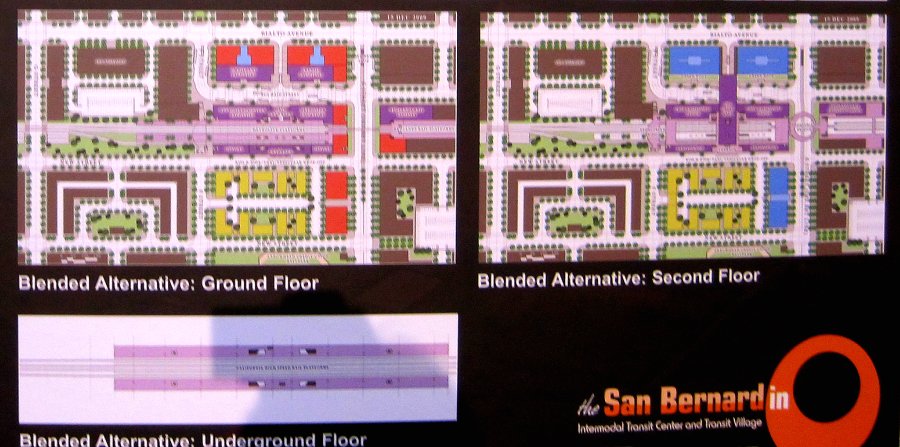

And pictures on Flickr! (Add this to the growing list of hideous proposed HSR stations.)

Beyond the lolz, it's nice to look at projects like these because they're perfect examples of precisely the sort of thing I'm trying to critique with this project, that is, overscaled transit-oriented development, normative mixed-use planning, and, quite frankly, bad urban design. If I suspected California developers would pounce all over HSR before, turning every station into another excuse for generic, lifestyle-center developments (see: Michael Sorkin and "Starbucks Urbanism"), this certainly confirms it. The last thing the Inland Empire needs is another stucco wannabe Rick Caruso project.

Of course these projects aren't all bad – clearly a step or two above the big box developments of the 1990s and the shopping malls of the 1980s – and their intentions toward sustainability and walkability are good things, even if their implementation is a little silly ("a dramatic open-air pavilion formed by giant ribbons of solar-energy collectors suggesting the prehistoric geological forces that shaped the valley"). Like the New Urbanism in general, is isn't the ambition that's bad (besides that whole weird selective nostalgia thing), but the methodology. Dropping clusters of condos and office buildings into the middle of the suburbs isn't the 'solution' to sprawl.

As the author of the comments that provided you such amusement, I must say that this entry in your 'b-log is mostly off-base.

ReplyDeleteMy quotation is being taken out of context since I was specifically referring to the San Bernardino terminal's design features that thoughtfully prevent sprawl, particularly by forming a nexus for enough transit modes and services to rival Hoboken.

San Bernardino was, historically, southern California's third urban core, and the multimodal terminal is an important piece in the city's plan, conceived by Vaughan Davies of EDAW-AECOM, to re-establish parity with Los Angeles and San Diego. To refer to San Bernardino as a suburb, therefore, reflects a lack of understanding of the context within which this station has been envisioned.

In fact, if you would like to know more of the larger plan, a quick search for "Re-establishment of Southern California's Third Urban Core" will provide you with a detailed summary of the actions taken thusfar to realize this goal, which has become necessary since, over the next 10-20 years, the San Bernardino Valley alone is expected to add another million residents to the four million who already live in the Inland Empire.

San Bernardino, the densest so. Cal. city East of Los Angeles and North of San Diego, is 200 years old, and it has the potential to become the most ecologically-sustainable city in the American Southwest due partly to its vast water supplies and to its extensive transportation infrastructure.

Additionally, the architectural character of the terminal is really yet to be determined, although the Vision & Action Plan for the city center establishes as a goal the juxtaposition of modern with traditional architecture to integrate heritage buildings into a dynamic and contemporary urban tapestry that is authentic and that avoids appearing like yet another "project." Several developers are sought, especially those that specialize in different types of construction, like student housing, T.O.D., adaptive reuse, etc.

Moreover, the mixed-income goals of the transit village make any resemblance to a Caruso project purely superficial. Realizing the highest standards in design and construction are absolutely essential to the strategy to reposition San Bernardino so that it competes with first-tier cities, and a fine-grained approach to this endeavor is the intention.

If you have any questions about the plan or if you'd like any more information, let me know. My address is zideaz(at)yahoo.com . Also, if you have constructive criticism, feel free to offer it to someone at Cooper Carry or Arup. Joe McClyde [ JoeMcClyde(at)CooperCarry.com ] is a staff architect working on the Intermodal Transit Center and Transit Village, and he's very interested in the storytelling and placemaking that you accuse this project of lacking.

In retrospect, I was being much too flippant and didn't really intend for my tone to be that dismissive or snarky – for that, I apologize. Obviously I agree with using intermodal transportation infrastructure to begin to a way to improve these sorts of urban conditions - that's the whole focus of my own project in Sylmar. And you're right, San Bernardino is less a suburb and more of an 'edge city', even though its density is, on the whole, rather low. It's these sort of urban fringe conditions that I'm most interested in. And since this San Bernardino project integrates multiple scales of mobility, it avoids one of the major dangers of these kind of stations, which I fear won't be the case in places like Palmdale and Visalia.

ReplyDeleteAs I said, I agree with the premise of the project, and I'm glad it's happening – better than nothing. That said, I do have serious problems with the way it's being done (beyond the aesthetics, though there's that too), which I suppose it's up to my own project to clarify. Of course I'll be approaching it from a completely different direction, but the important thing is that our goals are essentially the same.

I'm neither an architect nor a planner. And, I don't really understand the ways your project and the one in San Bernardino may differ. But, the fact that the conceptual block study and general layout were designed, in many ways, for the consumption of the California High-Speed Rail Authority Board is important to remember. It still hasn't made a determination as to whether or not a San Bernardino station is included in the L.A.-to-S.D. alignment. Considering, though, the amount of traffic and the number of modes the terminal is being designed to handle, it maintains a human scale and seems wonderfully-intuitive to navigate. In those respects, the facility really puts superblock and auto-oriented complexes, like ARTIC, to shame.

ReplyDeleteThe solar-energy collectors are also not merely an attempt to demonstrate a sustainability concept, nor are they simply a showy display of carbon neutrality. Rather, the roof of the building has the ability to power the very same trains that it hosts, thereby reinforcing the idea that these vehicles rely on sources of electicity that are renewable. Additionally, in this way, the cathedralesque train shed actually serves a purpose, instead of being purely ornamental.

In any case, the eastern half of the terminal is due to be completed in 2013 at a cost of a quarter of a billion dollars. So, if you have ways to improve the design, I hope you do let the architects know so that they can make this structure as successful as possible. However, I'm still having a hard time understanding the reservations you're harboring.

While you may object to the aesthetics of the terminal, itself, I suspect that you are more opposed to the "transit village," whose status, as such, enables it to qualify for additional government subsidization. Here, too, though, a human scale is emphasized through street-wall buildings created by multiple developers and organized around an impressive inventory of exemplary public spaces. San Bernardino is in the unique position of having an authentic urban environment with extensive infrastructure and existing density combined with copious amounts of vacant and underutilized land. So, since the municipality was, historically, transit-oriented and urban in its form, revitalizing the city center in this way is merely restoring elements lost in the post-war, freeway-dominated era.