Oslo Opera House

The 2010 European Prize for Urban Public Space was announced earlier this week and there are some great projects being honored, including the very high profile Oslo Opera House, pictured above, as well as some not-so-high profile ones, like this really lovely community garden in the 20th arrondissement.

Passage 56, Paris

And this fantastic library/park made out of parts from a demolished building:

Open-Air-Library, Magdeburg

The archives are well worth looking into, as well.

31 March 2010

Lisa Schweitzer is a little bit more cynical about HSR in California than I am — I recently had a pin-up with her to talk about my project and the real sorts of impact the proposed rail line is going to have on the urban fabric. She doesn't oppose the project as much as worry about how it could negatively affect existing transit funds - especially since the ridership is likely to be on the upper end of the scale, at least at first. (This post at Yonah Freemark's blog smartly addresses the issue of ticket prices, comparing prices on Acela, ICE, AVE, TGV, &c.) Her editorial in the Sacramento Bee addresses this, as well as offering what I think are some smart alternatives for CAHSR to "help ensure that the state's support for everyday transit does not disappear in the stampede to build high-speed rail." I'm not such a big fan of the first ones (should airlines really be the model for anything?), but she has, like, a PhD and stuff.

California today is nothing like Europe and Japan decades ago. We are spread out. We prefer our cars. Rail service would only help a small portion of the populace. The environmental challenges would be expensive and drawn out.

Umm, but the trains lose money and the people want their cars. To pay for that trip between SF and LA you would need to charge 3 times what plane fare would be.

At any rate, the comments are GOLDEN:

California today is nothing like Europe and Japan decades ago. We are spread out. We prefer our cars. Rail service would only help a small portion of the populace. The environmental challenges would be expensive and drawn out.

This is so wrong-headed it makes my head spin.

Umm, but the trains lose money and the people want their cars. To pay for that trip between SF and LA you would need to charge 3 times what plane fare would be.

You mean that subsidized plane fare? See also here.

Since when has high-density development boosted surrounding property values? An instant ghetto never does anything but drive people out of the neighborhood.

Since when has high-density development boosted surrounding property values? An instant ghetto never does anything but drive people out of the neighborhood.

Density = ghetto, apparently.

30 March 2010

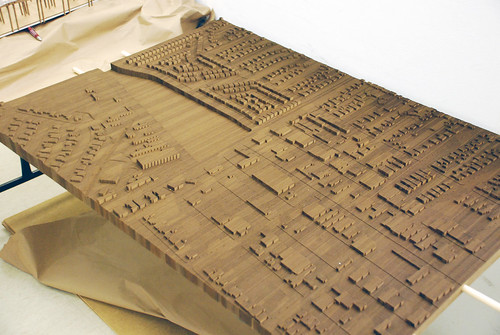

Photo from zIDEAz

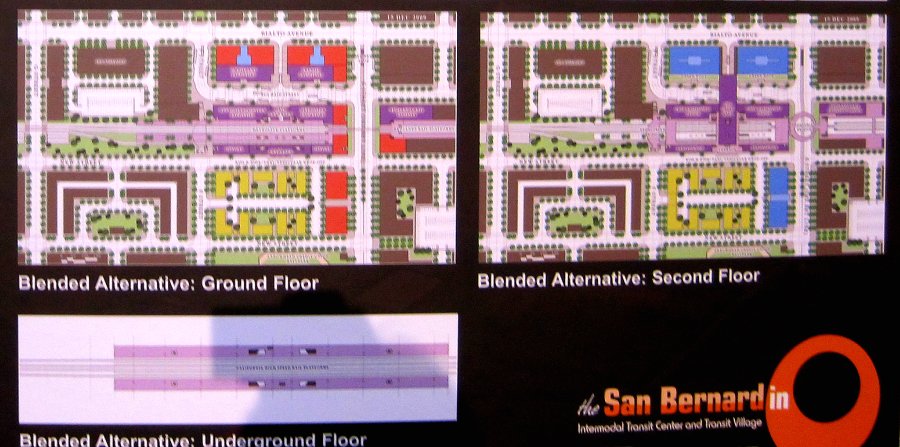

Every time I start to get discouraged with this project – thinking, perhaps, it's too obvious, self-evident, or unoriginal – I find things like this transit... center... thing proposed for San Bernardino. There's an (I think) unintentionally hilarious sales pitch in the comments at California HSR Blog:

San Bernardino recently unveiled plans for the best-designed high-speed rail station in California that has the capability of becoming a high-speed train hub for service to Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Anaheim-Long Beach, in addition to Los Angeles and San Diego.

Passengers will enter the terminal though the Great Hall, a multi-story concourse with ticketing facilities, escalators, and a green roof on the fourth level that will serve as a park offering dramatic views of the city’s mountains and skyline.

A Central Garden runs along the edges of all the at-grade tracks. Mixed-use development is seamlessly-integrated throughout the terminal with a residential emphasis South of the tracks and an employment emphasis North of the tracks. A generous amount of meeting and convention space is also included in the design. But, the complex does a remarkable job of amassing these facilities without creating a superblock since a network of interconnected streets are interwoven throughout the site.

And pictures on Flickr! (Add this to the growing list of hideous proposed HSR stations.)

Beyond the lolz, it's nice to look at projects like these because they're perfect examples of precisely the sort of thing I'm trying to critique with this project, that is, overscaled transit-oriented development, normative mixed-use planning, and, quite frankly, bad urban design. If I suspected California developers would pounce all over HSR before, turning every station into another excuse for generic, lifestyle-center developments (see: Michael Sorkin and "Starbucks Urbanism"), this certainly confirms it. The last thing the Inland Empire needs is another stucco wannabe Rick Caruso project.

Of course these projects aren't all bad – clearly a step or two above the big box developments of the 1990s and the shopping malls of the 1980s – and their intentions toward sustainability and walkability are good things, even if their implementation is a little silly ("a dramatic open-air pavilion formed by giant ribbons of solar-energy collectors suggesting the prehistoric geological forces that shaped the valley"). Like the New Urbanism in general, is isn't the ambition that's bad (besides that whole weird selective nostalgia thing), but the methodology. Dropping clusters of condos and office buildings into the middle of the suburbs isn't the 'solution' to sprawl.

24 March 2010

23 March 2010

21 March 2010

This is a fantastic conference; see especially Betty Deakin's presentation on TOD design for high speed rail in the Central Valley, which starts at about the 2/3rd point. She smartly points out that California, unlike France and Spain and especially Japan, is growing very rapidly; in addition, many of the cities in the Central Valley (and Sylmar, for that matter) have enormous amounts of empty space: empty parcels and large right-of-ways, all of which have a lot of potential, particularly in terms of dense infill development. But she also looks at the space between the buildings, including the much-too-wide streets and easements, as an opportunity, even an advantage, for urban design. This is a large part of my own design strategy, which I ought to be posting soon.

19 March 2010

As if any of these arguments haven't been made a hundred times, a few bloggers have been debating sprawl and zoning. It's worth a look:

Matthew Yglesias: Centrally Planned Suburbia

Randal O'Toole: A Libertarian View of Sprawl

Matthew Yglesias: "Libertarians", Sprawl, and Land Use

Kevin Drum: Zoning and Sprawl

Ryan Avent: Zoning and Sprawl

Kevin Drum: Sprawl Revisited

Ryan Avent: Zoning and Sprawl, cont.

Money quote, from Drum:

And now for a second point, even though I said I wouldn't make one: walkability is very difficult to create. It's not enough to build a bunch of houses with shopping nearby. It's not enough to have a few big apartment buildings. And there's no practical way to convert an existing suburb into a high-density area.

Well, yeah. Bringing density to the urban fringe is difficult (though still worth trying: see Retrofitting Suburbia and the recent Reburbia competition), not only because of zoning regulations, but also because of the social logic that underpins them: suburbia is a landscape of privatism and exclusion. Although it's true that the suburbs have become more and more diverse (including increasing poverty), they remain balkanized, as it were, and homogeneous on the neighborhood level. Suburbia is not merely the function of (artificially) cheap land and oil, and zoning is only a manifestation of deeper cultural issues: thus Fishman's thesis of suburbia as a cultural invention, which he traces back to the 18th century English bourgeoisie, who left the city specifically to circumvent public space. In my view, this is what begins to distinguish the suburban condition from genuine urbanity. And, as my thesis argues, before we try to address issues of walkability and density, architects and planners must examine urbanity and offer new solutions for public space in the suburbs.

More on sprawl and high-speed rail: Jason Kambitsis in Wired cautions that increased mobility and shorter travel times between the core and the fringe might encourage sprawl; Yonah Freemark smartly responds (short version: ticket prices will make HSR commuting unrealistic to all but the wealthiest). HSR is obviously not aimed at daily commuters, but rather travelers. For my project, the layering of bus networks, commuter rail, and long-distance high speed rail is the crux of the argument.

15 March 2010

This is quite odd: a (rather hideous) design proposal for a high speed rail station in Sylmar from 1995? I hadn't realized Los Angeles was planning any HSR as far back as then. No wonder the eyes of all the urban planners I've talked to glaze over as soon as they hear anything about high speed rail.

13 March 2010

Preface: I love Street View. I love transit. It's the first day of (my last?!) Spring Break, and instead of going on a road trip to Santa Fe with my friends, I'm in bed with a cold. Indulge me.

View Larger Map

Blue Line in Los Angeles. This is "light rail" but acts much more like heavy-rail or commuter, certainly closer to BART than Muni Metro. In other words, it's not always clear what the difference between the Red and Purple lines and the Blue and Gold lines is, other than the former two are underground and the others aren't. Also: why are the trains so ugly? I don't know. This section, along Washington Blvd, could be quite nice but isn't. If Caltrain : Metrolink :: BART : Metro, why does Los Angeles have no equivalent to Muni Metro? Metro Rapid hardly counts, and the Orange Line, though successful in many ways, is weirdly tucked away behind bushes.

View Larger Map

N Judah line in San Francisco. These streets aren't particularly wide, either; Los Angeles boulevards like La Cienaga or Normandy or Santa Monica could easily accommodate rail like this, I think.

View Larger Map

Portland Streetcar. Trams like this are smaller, require smaller platforms, and have lower capacities, but run quite a bit more frequently than proper light rail. The Portland Streetcar is being adapted to downtown Los Angeles, linking the Historic Core, South Park, LA Live, and the Music Center (ish), which seems like a perfect loop, and just the sort of range for a streetcar, as well as a good foundation for what could be an expanded network to replace the DASH buses (extending to Chinatown, Little Tokyo, City West, USC/Exposition Park, &c).

View Larger Map

Portland MAX. In Portland, the light rail and streetcar systems interface quite well, intersecting downtown near Pioneer Square. The light rail works similarly to the streetcar downtown and later operates in dedicated right-of-ways and stopping less frequently. This adaptability would be perfect for Los Angeles, as density is sometimes very high and then quite low. A system that operated more like a tram in, say, Santa Monica and more like light rail in Brentwood seems ideal.

View Larger Map

Tramway des Maréchaux, Paris. This is my favorite line. Technically a tram, the cars have seven sections, allowing high capacities, and the dedicated, grassy right-of-way allows it to move fairly quickly; this seems to me to combine the best of tramways and light rail, and seems applicable especially to broad boulevards (like Sepulveda, for example, which used to have a Red Line route down the middle anyway).

View Larger Map

Trambesòs along Avinguda Diagonal, Barcelona. Along the Diagonal, it runs in a grassy strip similar to the Maréchaux in Paris. Between the two directions there is a long, tree-lined pedestrian promenade, forming a sort of linear park running from Gloriès to the Forum.

View Larger Map

Tramway in Strasbourg (Homme de Fer). Those Citadis trams are so pretty! Contrast with the Blue and Gold lines, and, doubtlessly, the Expo.

View Larger Map

Line 8 in Rome (in front of San Carlo ai Catinari, on of my favorite churches in Rome).

View Larger Map

Tramway in Bordeaux. Bordeaux and Strasbourg show quite well how nonintrusive these lines can be in the urban fabric. Quieter and cleaner than buses, obviously. There was quite a bit of fuss about the Expo Line crossing in front of some elementary schools. Certainly, as there have been many accidents along the Blue Line, the school board is justified in its concern, but banishing the trains underground (at great expense) hardly seems to be the answer. No one is afraid of the light rail/tramways in Zürich or Vienna (or, as my friend Christina points out, in Portland); they run along the sidewalk, sharing the road with pedestrians, bicyclists, cars, and buses.

View Larger Map

Straßenbahn in Zürich (Schaffhauserplatz). Now we are getting to more bus-like systems: streetcars rather than light rail, strictly speaking. Still, run frequently enough, they seem to be able to move people as efficiently as heavier systems, and must be much cheaper to operate. Using curbs as platforms and simple shelters rather than "stations" is clearly a huge advantage.

View Larger Map

Awesome olde-timey streetcars in Milan.

Lest you think I'm too eurocentric:

View Larger Map

Scandalously ugly tram in Melbourne. But the Melbourne system testifies to the advantages of a large, interconnected network of trams. One can imagine Los Angeles, with its relatively straightforward grid of boulevards, with a network as dense as Melbourne's (which has half the population density of Los Angeles).

02 March 2010

Because Michael Sorkin's "The End(s) of Urban Design" from HDM 25 has been such an important part of my research, I found this exchange particularly interesting:

[William] SAUNDERS: [...] there is a mom-and-apple-pie set of principles that, rightly, no one takes exception to, things like mixed uses, pedestrian scale, banishing automobiles as much as possible, good public transportation, retail open to streets, street trees, etc. [...] Sorkin points out that all this offers a rather pathetic form of public life centered around comfortable hedonistic lifestyle mainly for shoppers enjoying their cappuccinos and their chance to buy Gap clothes, and if that's urbanism, we're screwed, because it doesn't have anything to do with political life or social integration.

[Margaret] CRAWFORD: Sorkin's attitude is typical among certain leftists who haven't examined real behavior in the city—there are now lots of paradoxes about what is public and what is private [...] The idea that only the raw city is authentic expresses a kind of Puritanism about pleasure: what people want in public space is pleasure.

[Rodolfo] MACHADO: Sorkin's position seems very '60s.

CRAWFORD: It's so '60s.

[Paul] GOLDBERGER: It is as retro as the New Urbanism.

CRAWFORD: [...] there are two kinds of public space: the agora, the very small public space of democratic interaction; and the cosmopolis, where difference is visible; and Sorkin is conflating the two, imagining that somehow a diverse public equals a public of democratic interaction. They're quite different, although they are not mutually exclusive. [...] In Central Square, The Gap is a social condenser that mixes publics under the sign of consumption.

SAUNDERS: I'll just say that if I'm in a city and my only option is to shop and not go to museums or anything like that, I want to go home.

(Farshid) MOUSSAVI: The Tate Modern sells more per second that the Selfridges department store in London.

from "Urban Design Now", same issue of HDM.

[William] SAUNDERS: [...] there is a mom-and-apple-pie set of principles that, rightly, no one takes exception to, things like mixed uses, pedestrian scale, banishing automobiles as much as possible, good public transportation, retail open to streets, street trees, etc. [...] Sorkin points out that all this offers a rather pathetic form of public life centered around comfortable hedonistic lifestyle mainly for shoppers enjoying their cappuccinos and their chance to buy Gap clothes, and if that's urbanism, we're screwed, because it doesn't have anything to do with political life or social integration.

[Margaret] CRAWFORD: Sorkin's attitude is typical among certain leftists who haven't examined real behavior in the city—there are now lots of paradoxes about what is public and what is private [...] The idea that only the raw city is authentic expresses a kind of Puritanism about pleasure: what people want in public space is pleasure.

[Rodolfo] MACHADO: Sorkin's position seems very '60s.

CRAWFORD: It's so '60s.

[Paul] GOLDBERGER: It is as retro as the New Urbanism.

CRAWFORD: [...] there are two kinds of public space: the agora, the very small public space of democratic interaction; and the cosmopolis, where difference is visible; and Sorkin is conflating the two, imagining that somehow a diverse public equals a public of democratic interaction. They're quite different, although they are not mutually exclusive. [...] In Central Square, The Gap is a social condenser that mixes publics under the sign of consumption.

SAUNDERS: I'll just say that if I'm in a city and my only option is to shop and not go to museums or anything like that, I want to go home.

(Farshid) MOUSSAVI: The Tate Modern sells more per second that the Selfridges department store in London.

from "Urban Design Now", same issue of HDM.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)